Dear community,

Schizophrenia is still the most stigmatized mental health condition. And many people don’t realize that it can be effectively treated.

💫Spread the light with Dr Devika B. First-person accounts of living with mental illness that dispel stigma and stereotypes and instead, spread hope and light — also a YouTube channel and podcast called Spread the light with Dr Devika B (wherever you listen to podcasts, including Apple and Spotify)

Because stigma festers in the dark and scatters in the light

Hear more about how schizophrenia recovery works directly from Brandon Staglin.

Brandon’s journey with schizophrenia started in 1990 — and today, he serves as President of the mental health non-profit One Mind and thrives as a leader, advocate, husband, and musician. At One Mind, Brandon channels his deep expertise in communications, advocacy, and his personal recovery from schizophrenia to drive advances in brain health research and services.

If you’d prefer to watch our conversation, you can do so here.

Trigger warning: In this interview, we talk about psychosis and suicidality.

If you or a loved one needs help for a mental health crisis, don’t hesitate to call or text 988 at anytime — or reach them online here. Find other resources here, search for a US treatment facility here, and find a US-based therapist here.

Wishing you light,

Dr Devika Bhushan

DB: How did your mental health journey begin?

BS: I was diagnosed with schizophrenia when I was 18 years old, back in 1990 and it was the scariest experience I'd ever had.

I had been in college for a year at that point, and that year had been very stressful. I had experienced a bit of a culture shock at Dartmouth. I didn't feel like I fit in very well. Academics were challenging. And I met my first serious girlfriend there — we had a terrible breakup toward the end of that year. And I was looking for my first competitively placed job that summer; I wasn't finding anything.

All these thoughts were kind of wheeling around in my head: Am I worthy of love? Am I worthy to succeed in life?

All that stress came to a head one night when I was trying to fall asleep and thinking about these things, and it was like something snapped within me.

The sensations were bizarre: It's like half of my awareness had vanished and in its place was this dark, swirling vortex of dread. And all the love that I felt for my family, my friends, my ex-girlfriend, I couldn't access any of it then. And it was all unfamiliar, so that was terrifying in itself.

And I was convinced that if I let any new experiences enter through the right half of my body — like my right eye or my right ear — that a new personality would develop inside me and kind of take me over.

This was a terrifying delusion, which is typical with schizophrenia. People experience these beliefs that something is true, which is clearly not for anyone else.

I couldn't sleep all that night or the next five nights.

I fortunately was able to get to a psychiatric hospital with the help of a friend.

And my parents didn't know about what had happened to me at that point. They were away on a trip — they found out from a neighbor who'd seen me go to the hospital in an ambulance.

They came back as soon as they heard. They took me back home and found a psychiatrist that I could trust after a couple of tries.

And that's when my recovery began. And there were some very dark times in my early recovery; I was close to suicide on multiple occasions.

I was able to recover well enough to go back to college about six months after my initial episode, thanks to getting treatment early.

And also thanks to the loving and dedicated support of my family, who made sure I knew that they loved me unconditionally. That gave me strength.

And want to continue working for my own recovery — and stay involved with the community, doing things that mattered to me and were meaningful for others, as well. It gave me a sense of purpose.

So those things, plus the ambition that I had to continue on in my career, drove me to recover and go back to college.

DB: How has stigma has affected you?

BS: Sharing my story humanizes the experience of somebody with schizophrenia. I aim to help dispel the stigma around schizophrenia. It's still the most stigmatized mental health condition.

The worst stigma for me was initially the self-stigma. And it drove me, during my early recovery, to not tell anybody that I knew, except for very close friends and family.

Back at college, I was constantly policing my thoughts and my feelings and my behaviors. As if, if any weirdness leaked out, that people would know what happened to me that summer. And they would ostracize me. That was exhausting — thinking that all the time.

I ended up isolating more than I should have. That was not good for my mental health and well-being.

Around cultural stigma or public stigma? It's typically it's been a little bit less.

During my second episode recovery in the mid-1990s, I was trying to make new friends again.

My family had founded One Mind in 1995, inspired by our shared experience with my schizophrenia to fund and improve research for new treatments. So my story had been published in the newspaper.

Because my story was known to the new people in my social circle, some of them were discriminatory; some of them made fun of me and played jokes on me. And I felt marginalized. I felt ashamed. I thought, ‘Are these really friends? Maybe they're not.’ All the hope that I had to make friends had been dashed.

But more recently, I figured out how to overcome stigma by speaking about my condition with conviction and framing it as a strength.

I find that when I speak about it matter-of-factly and highlight what I've learned from my experiences with the condition, people are much more receptive and appreciative that I'm sharing and ask me a lot of questions. They're very interested.

And actually, I applied to graduate school in 2017, to get a Master of Science in Healthcare Administration and Interprofessional Leadership at UCSF.

And at that point I was debating with myself, ‘Shall I disclose on my application that I live with schizophrenia?’ I decided, ‘I'm all in — I'm going to do this.’

I framed it as a strength and highlighted what I learned from my condition and how it would help me be a better healthcare leader.

And it worked — I got in. With very supportive faculty and cohort, I had a great experience at UCSF.

DB: With schizophrenia in particular, stigma has been on the rise in the last few years, rather than on the decline. Where do you think that comes from?

BS: I think there are the three main reasons.

Number one is that the media typically blames mental illness for violence that takes place in society. And that can perpetuate discrimination against people with mental illness.

People in treatment for mental illness, when they're getting good treatment, typically are no more violent than any other part of society.

And it's more likely that somebody's going to be the victim of violence if they live with a mental illness than to be violent themselves. I think that's important to understand.

Secondly, psychosis, which is a key feature of schizophrenia — that's the hallucinations that people experience, like seeing or hearing things that aren't actually there — they are not understandable by anyone else in the world.

Those are really hard for people to identify with. And so they lead to a sense of othering of people who experience these things.

And then the third factor is something that One Mind's Director of Clinical Programs, Irene Hurford, MD, has mentioned: when we encounter somebody with psychosis, if we haven't experienced it ourselves, it underlines that everyone's grip on reality is a little bit tenuous. I think that unsettles people.

DB: Looking back at the hardest parts of your journey, what is one thing that you would've told yourself then?

BS: I would've told myself: there is still a ton of potential in life, even with a schizophrenia diagnosis.

And that there's a lot to learn from experiences with a severe mental illness, like with many types of adversity.

I think that if I had known that, it would’ve bolstered my hope.

I would've wanted to tell myself about all the great things I could have — and in fact, have experienced since then — by holding on and continuing on with my dreams and plans and goals. And continuing to be a part of a family, part of a circle of friends, part of a community.

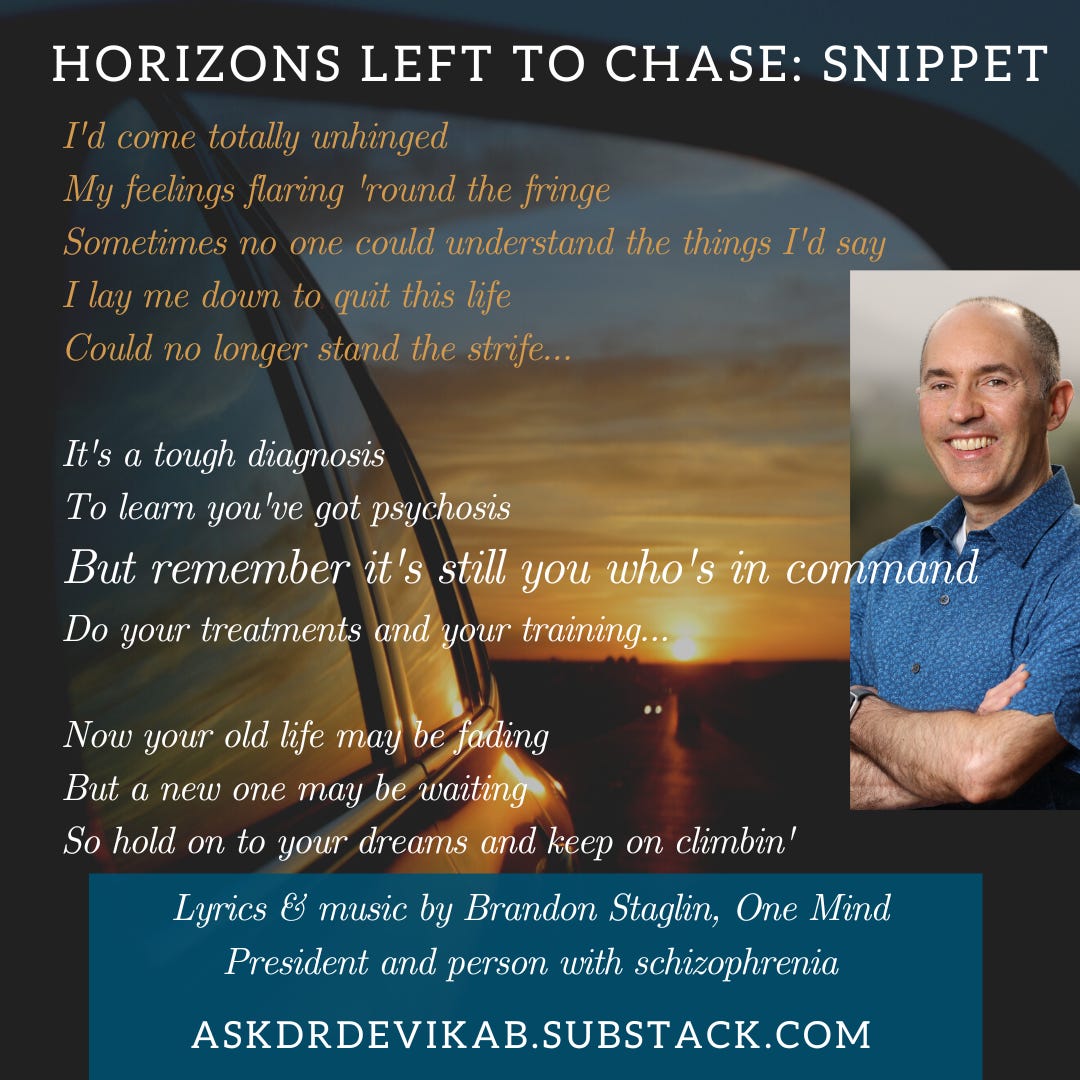

I actually wrote a song about recovery from schizophrenia: it's called Horizons Left to Chase.

It’s all about the potential that remains in life or even is it amplified in life after a severe mental illness diagnosis.

DB: How has your journey shaped your unique superpowers?

BS: I've learned a lot of compassion. It means a lot to help people with their health and well-being. That means the world to me that I can do that and be there for them: my wife, my family, people that I work with. It gives me a strong sense of identity and meaning.

And on top of that, the conviction that there can be a better world, there can be a better life for people who experience serious mental illness. I've been able to grow into such a life, and I feel very fortunate.

It shouldn't be a lucky thing. It should be a commonplace thing that when somebody develops a schizophrenia or any other serious mental illness, that recovery can be within their reach.

I'm working hard to make that a reality. And that gives me a sense of purpose, too.

DB: What's one mental health myth that you would like to bust?

BS: I would want to emphasize that even a schizophrenia diagnosis is not a death sentence. It doesn't mean you're sidelined for the rest of your life.

I think that's really important to understand. Recovery can happen and people who experience schizophrenia are human beings.

To quote my friend Elyn Saks, a wonderful advocate and a law professor at USC who lives with schizophrenia, from her book, The center cannot hold: My journey through madness: “the humanity we all share is more important than the mental illnesses we may not.”

That's a wonderful thing to remember — we're all human.

DB: You've now lived with this diagnosis for three decades and more. What are your strategies for staying well?

BS: There are three main things that I do.

One is to exercise every day. That lifts my mood and gets my brain active for the day.

Second, getting enough sleep. I find that when I get too little sleep repeatedly, I can't process information very well. I can't make good decisions and I can't relate to people with the kind of empathy that I’d like to.

And thirdly, I meditate every morning. It quiets my mind and gets me open to the possibilities of the day. And that gives me a sense that anything is possible.

And then there's social connection, which is prime.

DB: What are your hopes for our collective future?

BS: I'm excited that there is so much momentum building for change in the mental health sphere.

One Mind's just launched our accelerator program, which will help entrepreneurs launching startups to help people with serious mental illness. We have chosen 10 companies out of over a hundred applicants.

When a company gets behind a problem, it can access more funding than a nonprofit typically can. This is our way of accelerating our impact as a nonprofit — by helping startups to accelerate their impact.

When government, nonprofits, and private industry work together, we can make a big difference for people who are struggling with mental illness. I'm excited to be part of that.

Spread the light: Brandon Staglin's journey with schizophrenia