Deep dive, stress and health part II: Turning off the stress response in the moment

Stress and health mini-series: Part II of IV

Dear community,

This past week saw a particularly horrific spate of US child deaths by gun, and I’m sending love to all of you in their wake. There really are no words to describe the horror.

There were some wins, too, last week:

Senator John Fetterman returned to Congress and family life after 44 days of inpatient treatment for depression — about which he was heroically open — to a standing ovation.

President Biden signed an Executive Order authorizing over 50 actions designed to expand access to care of all kinds, reduce costs, and better support caregivers, including those providing unpaid care at home.

How are you doing with respect to your stress temperature?

For me personally, the next 5 weeks have the potential to be particularly stressful, with 8 (!) in-person speaking events; new medical procedures to navigate; and a big move, as we wrap up our home in SF to transition to a nomadic existence June onwards.

So I’ve had to intentionally break out many of the tools we present here this week, and it’s definitely been a work in progress. Some days, I’m more conscious of the anxious, fear-based thinking and knots in my shoulders — and other days, I’m able to lead from a place of balance, optimism, and certainty. Being aware of how the stress response is showing up for me from moment to moment and how to guide it to be helpful rather than harmful makes all the difference.

My hope for our community is that the bite-sized, actionable principles we present in this four-part series on stress and health will empower each of us to better steer our bodies towards a healthier response to stress now and in the future, ultimately allowing us to lead healthier and more satisfied lives.

In this four-part Deep dive miniseries, my colleague, Dr Gilgoff, and I break down:

I: Stress and health — the basics: article | video

II: Turning off the stress response in the moment (today): article below | video

III: How to reverse the health impacts of stress: article | video

II and III+: My personal favorite ways to destress: article

IV: Supporting a loved one after a traumatic event: article | video

Dr Rachel Gilgoff is an integrative medicine specialist, child abuse pediatrician, Stanford stress researcher, science writer, and mother of two amazing kiddos. She is dedicated to improving care for stress-related health issues and promoting lifelong health and wellness.

Dr Devika Bhushan is an equity- and resilience-focused pediatrician, public health leader, parent, and Indian-American immigrant who served as California’s Acting Surgeon General in 2022.

A modified version of this article also appears on the American Academy of Pediatrics’ parent-facing website, healthychildren.org.

Will you be at the Pediatric Academic Societies meeting in DC this week? Come say hi! Both Dr Gilgoff and I will be there, presenting a framework for addressing toxic stress within pediatrics.

Wishing you light,

Dr Devika Bhushan

PS: We are experimenting with different days to send out this weekly newsletter to best meet our community’s needs. If you have strong feelings on the matter, please let us know here.

How do we turn off our stress responses in the moment?

Our stress response system gets activated in small and big ways all the time — and while this can be helpful, in many instances, it can also make us feel and act in ways we would rather not — whether that’s losing our cool or feeling overwhelmed and paralyzed at what’s ahead.

Knowing that there are strategies at our disposal to actually help us turn off the biological stress response in the moment and regain rationality, balance, and cognitive flexibility can be really empowering.

The techniques we share here can be helpful for any of us — from very young children to adults. Certain strategies are particularly useful for supporting a child or other loved one through an activated moment (marked ^) — and the others are useful universally.

When emotions take control: ‘flipping your lid’

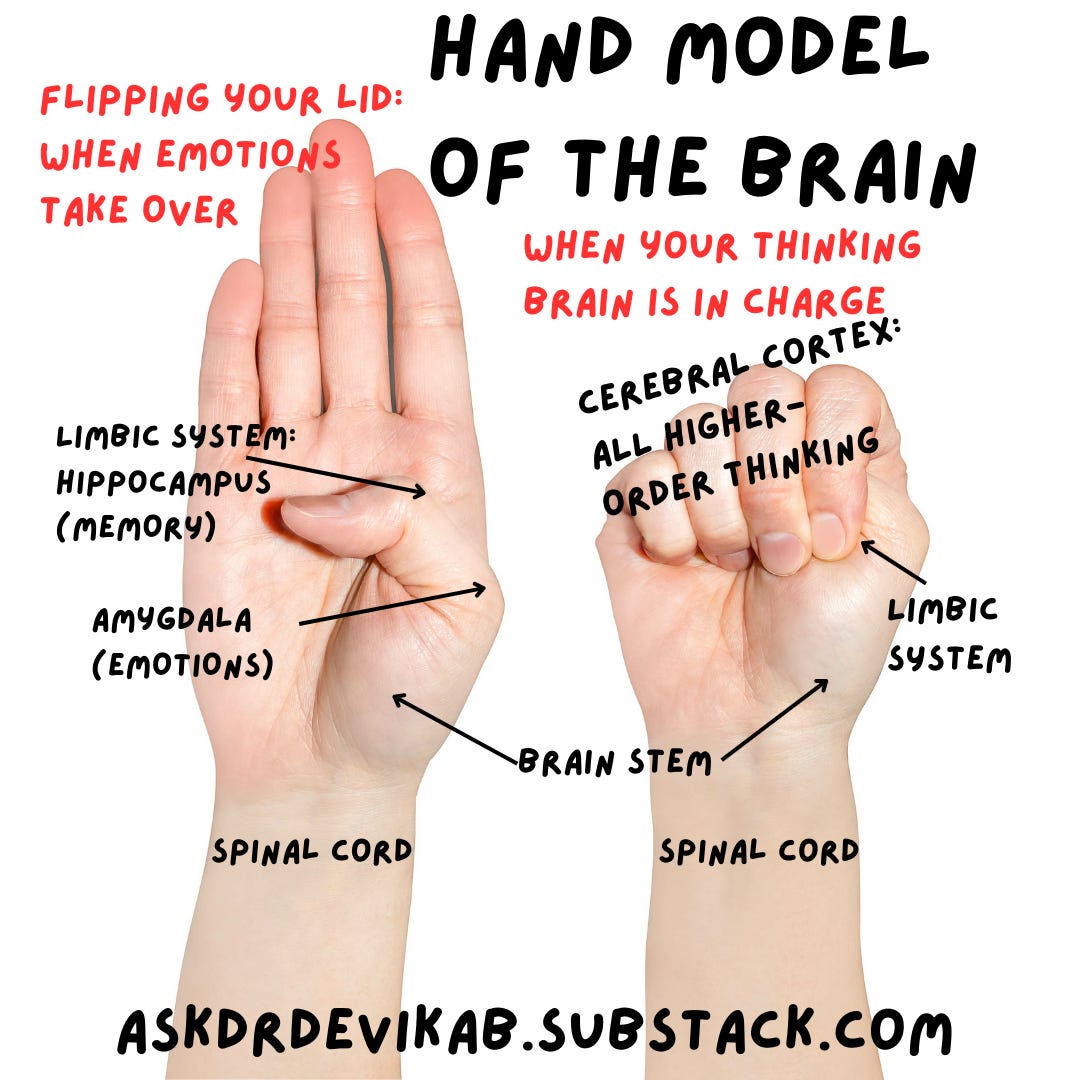

We sometimes use a hand model of the brain to help visualize what’s happening when the stress response knocks our ‘thinking brain’ out of the way.

The fingers, folded over the thumb, represent the prefrontal cortex — the upper or thinking part of the brain. The thumb represents the limbic system, including the amygdala or ‘emotional brain,’ which controls the freeze or flight-or-flight stress responses (more on those here).

A strongly activated stress response can make it so the ‘emotional brain’ flips the ‘thinking brain’ out of the way and takes over.

Here are some signs we’ve ‘flipped our lids’: freezing, ‘spacing out,’ being irritable, or volatile emotions. Kids might show signs like ignoring , temper tantrums, slamming doors, hitting, or kicking.

Learning to manage the stress response

We can bring our ‘thinking brains’ back in control if we have the skills to manage the situation and calm the stress response. Most of us don't initially — and it takes practice to learn how to deploy these tools in the moment. The more we practice, the better we get.

It’s also never too early to learn these skills — so if you have a child or other loved one in your life, you can help them practice these, too.

A few special notes about supporting children through stressful experiences:

Particularly after stressful events, children often communicate their needs to us through their behaviors instead of words. They don’t yet have the language or tools to tell us exactly what is going on inside. When a child is ‘acting out,’ there’s a good chance they’re feeling overwhelmed and stressed and don’t yet have the skills to manage the situation or their stress response. Their behaviors give us clues as to which skills they may still need to learn—and then we can help them do so.

Strategies to tame the stress response

The brain processes information from the bottom up — from the most basic to more complex functions. This means that the regulatory (instincts and automatic functions such as heart rate) and relational parts of our brains will be the first parts to process and respond to what we experience.

To most effectively reach anyone who is stressed (child or adult), use neuroscientist Dr. Bruce Perry's 3 Rs framework: Regulate, Relate, Reason, to tap into our brain functions in the order in which they activated. (Read more about this here.)

A. Regulate: First, we have to regulate or calm our stress response (and/or that of your loved one).

B. ^Relate: Then, if you are supporting someone, relate to how they’re feeling. Help them feel seen.

C. Reason: Once there’s safety and understanding in place, process what happened through reason.

A. First, REGULATE: Calm the stress response

When possible, as a starting place, reassure yourself (and/or the person you’re supporting) that you are safe in the here and now. Then, use the techniques below to help return the stress response to baseline.

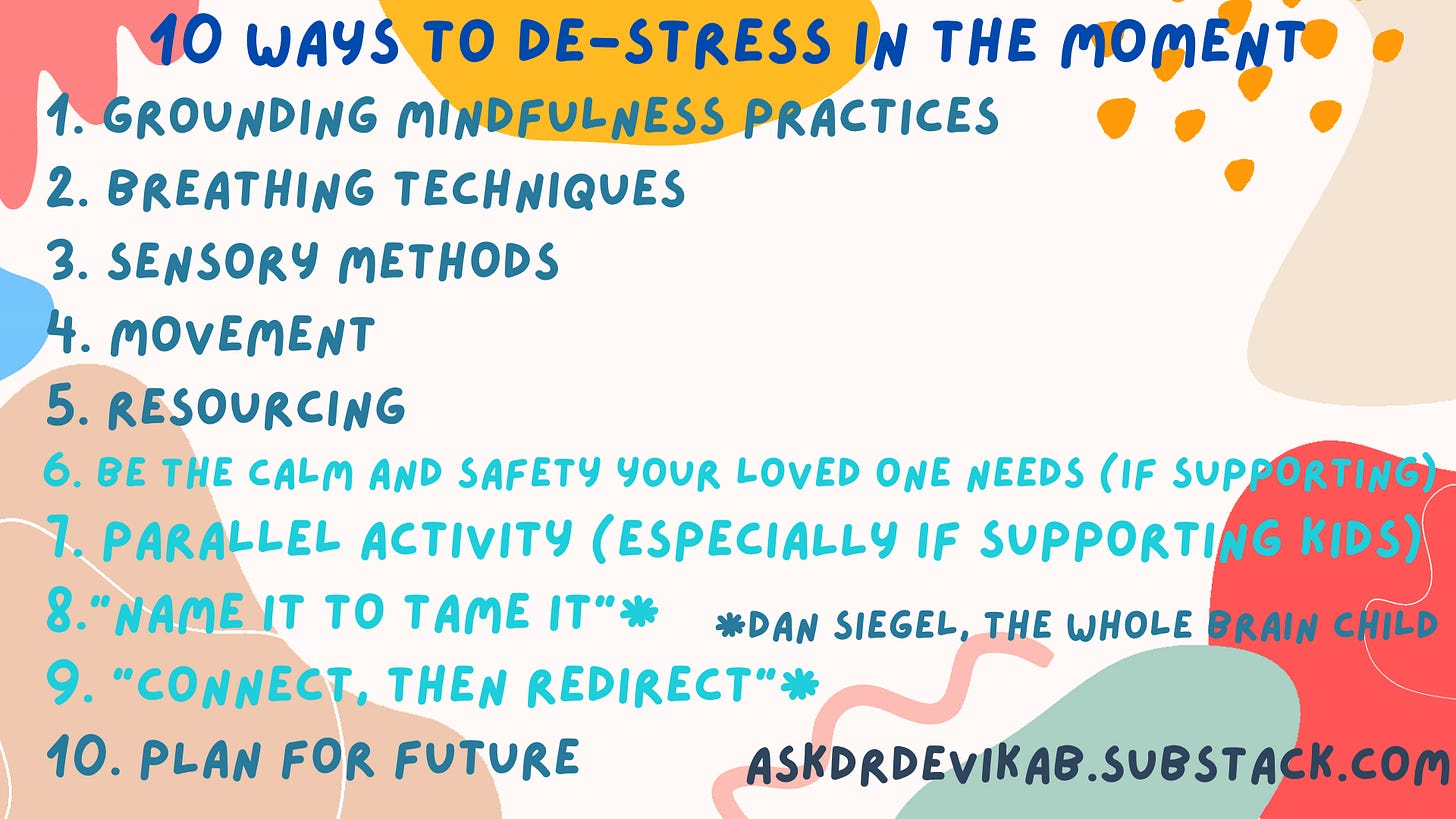

1. Try grounding mindfulness practices

Feel your feet on the floor, your back on a wall, your arm on a chair rest.

Use your five senses: Notice 5 things you can see, notice 4 things you hear, notice 3 things you touch, notice 2 things you smell, notice 1 thing you taste

2. Use breathing techniques

Slow, long exhalations slow our heart rates down and calm our stress response. Try:

Putting your hand on your chest and belly to focus on your breathing

Children can try: belly breathing with Elmo or with Rosita

3. Explore sensory techniques

These rhythmic, sensory activities can soothe our stress systems:

Drink water (sucking and swallowing is one of the most basic calming skills we have from birth)

Rock back and forth

Listen to music

Massage your own hand or body

Consider tapping techniques, a type of acupressure meant to help manage stress: like patting your thighs with your hands

Hug or cuddle with a loved one

4. Try some movement

Moving our bodies can help release stress energy or help rev up a system that may be depressed or down. Consider:

Walking or jogging

Jumping jacks

Dancing

Stretching or yoga

5. Resourcing

Plan ahead: When you’re in a calm place, think of a person, place, thing, or memory that makes you feel calm, strong, or happy. Practice visualizing that person, place, thing, or memory. The more specific the sensory details, the better this works.

Then, when you’re having a rough moment, you can connect with that resource, either in your mind or if possible, even in real life.

To help regulate a loved one (like a child), try these:

6.^ Be the calm they need

If you’re leading an activated loved one through these skills, first, try to exude the calm they need. This can be incredibly hard to do in the moment. If you’re upset or activated, use the strategies below for yourself before engaging with your loved one.

7.^ Look for parallel activities

Ever notice how kids seem more relaxed and talkative in the back seat of the car or when you’re walking side-by-side? Depending on the person, eye contact or face-to-face interactions can sometimes be particularly stressful when we are already feeling activated.

Consider positioning yourself to the side or lower than your loved one to help decrease their activation. Also consider other parallel activities that you can do together to calm the stress response, such as:

Coloring or making art

Walking

Playing with toys

Washing dishes or cooking together

Going for a drive

B. RELATE: Connect

If you’re supporting someone else through a stressful moment, try these techniques to relate to their experience, after you’ve helped them regulate their stress response. You can read more about them here.

These also work nicely when used solo — often with the help of a journal or other tool.

8.^ “Connect, then redirect”

When a loved one is struggling, it helps them to feel seen and heard, for us to empathize with their situation, be curious, and ask questions. Knowing we are attuned to their emotional needs enables them to feel safer and calmer.

Once they do, if needed, we can then redirect the conversation to next steps, like safety planning or practicing coping skills.

When working through something on your own, make sure to hold space to validate how you’re feeling — feeling activated by something that feels like a threat is natural.

9.^ “Name it to tame it”

Naming our emotions can help us tap into how we’re really feeling (which can be hard), to feel more in control with those emotions, and to know how to proceed.

Give yourself space to figure out what you’re feeling now that your stress response is less activated: Maybe take a walk to noodle on it, write some thoughts down, or consider them out loud with yourself or a trusted other.

If you’re supporting someone else, you can help them identify how they’re feeling, too. Sometimes naming what you think you see can help — saying something like, "You seem really frustrated or angry right now. Is that right?" This can work for all ages — toddlers to adults!

C. Finally, REASON

10.^ Process and plan for future

Once you’re feeling safe, regulated, and understood, you can move towards using higher-order thinking to problem-solve and build longer-term skills to cope with stress now and in the future.

When you’re ready, consider these questions:

What were the triggers that led to the stress behaviors?

What helped you feel better this time?

What are your strengths that you could draw from next time to cope?

What supports do you need to feel safe in the future?

What skills might you want to learn to feel more in control and better able to cope with that trigger or stressful experience next time?

Have you used any of these techniques before?

What’s worked especially well for you?

What’s new for you here?

What are you most likely to try out next when you need it? Let us know in the comments!

Get excited! Our next Spread the Light guests will be: Andy Dunn and Lisa Ling

What questions do you most want me to ask Andy and Lisa? Send them my way!