Dear community,

This month, in honor of the inaugural Health Workforce Well-Being Day on March 18th, commemorating the day the President first signed the Lorna Breen Act into law in 2022, I’m thrilled to feature conversations with three brilliant national leaders who are transforming health worker well-being.

💫 Spread the light with Dr Devika B. Conversations that dispel stigma and stereotypes and instead, spread hope and light — also on YouTube, Apple, Spotify

Because stigma festers in the dark and scatters in the light

More about our speakers:

Corey Feist, JD, MBA, CEO and co-founder of the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, founded in 2020 to address the systemic drivers of health worker ill health and honoring Dr Lorna Breen, a frontline emergency room doctor and Corey’s sister-in-law, who died by suicide. The work of the Foundation was recognized by the US Surgeon General’s Medallion Award in 2023 and I’m proud to serve as an Ambassador.

Mona Masood, DO, the psychiatrist who founded the Physician Support Line, staffed by volunteer psychiatrists to extend free, 1-1, anonymous support to physicians and medical students, starting in 2020.

Janae Sharp, CEO and founder of the Sharp Index in 2018, with a vision to make health care “the healthiest place to work,” and to prevent physician suicides like that of her ex-husband, Dr John Madsen.

Trigger warning: In this episode, we talk about systemic challenges inherent to working within the US medical system and their mental health consequences, including burnout and death by suicide.

Above, you’ll find the audio recording of the podcast episode and below, a transcript. The written conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length. If you’d prefer to watch this conversation, please click here. Here’s a brief video clip:

Catch other parts of our mini-series on health worker well-being:

Chief Wellness Officer Dr Jessi Gold on optimizing health worker well-being

Psychiatrist Dr Ahmed Hankir’s journey with melancholia and elation in medicine

Psychiatry resident Dr Jake Goodman’s journey with depression and anxiety in medicine

Nephrology fellow Dr Justin Bullock’s journey with suicidality and depression in medicine

Emergency resident Dr Ade Osinubi’s journey with hopelessness in medicine

Understand the key issues — Deep dive: Clinician well-being

Click here to catch up on other Spread the light columns, in addition to other posts organized by column type, going back to our newsletter’s launch in January 2023.

If you or a loved one needs help for a mental health crisis, don’t hesitate to call or text 988 — or reach them online here. Find other resources here, search for a US treatment facility here, and find a US-based therapist here. If you’re a US-based clinician or health student dealing with “any issue, not just a crisis” — reach out to the Physicians Support Line, free of cost and confidentially: 888-409-0141 (M-F, 8 am to 12 am ET).

Wishing you light,

Dr Devika Bhushan

DB: First up, we’ll hear from Corey Feist. I’m moved and inspired by the work you're leading, and I wanted to have a chance to get your perspectives and vision on record.

CF: Thank you for that — thrilled to have a conversation.

I also just make a note: thank you for being vulnerable and sharing your own mental health challenges. Because I think it is critically important that clinicians at all levels openly talk about these issues.

What we've learned over the years is: When you speak of the unspeakable, it gives permission to others to speak about it, too.

It's easy as putting a signature block on the bottom of their email that says, 'in therapy since...' or 'medicated for XYZ since...' — little things like that all chip away at this stigma.

DB: I love how you put that: Speaking of the unspeakable to make it an easier and more normalized experience for others. Corey, I'm curious if you could give us a sense of how you came to this work.

CF: You know, I spent my whole career in health care, first as an attorney, and then as the CEO of the University of Virginia Physicians Group. I moved from being on the hospital side as a lawyer to then a policy person and then an operations leader.

So that my professional upbringing and my entire career has been in healthcare, really looking out for the impact of the increasing demands, around EMR and other administrative burdens, on the time of clinicians. And I saw over the last 20 years: this incredible work shift and burden shift across the clinicians whom I represented.

And then, in the spring of 2020, we made national news when my sister-in-law, Dr Lorna Breen, died by suicide. Lorna was an emergency medicine leader and a practicing clinician in New York City, and had a singular mental health episode following a really horrible bout with COVID and then returning to the workplace too early. And [she] was so burdened by stigma, both the perceived stigma of her peers and her colleagues, as well as the structural stigma, which she believed was around penalties for obtaining mental health care. That this incredibly bright, vivacious 49-year-old getting her MBA, taking the world by storm, living her dream, amazing human decided to take her own life... And the response by the workforce to her death, the publicity around her death — publicity we never asked for. We found Lorna's story on the front page of a couple of New York City newspapers 12 hours after she died.

And we were so incredibly just overwhelmed with loss and grief. And then in this moment of clarity, my wife, Jennifer, and I decided that we really needed to share the story of this amazing, amazing human.

And we never would have imagined the response by the healthcare workforce to that story. With my professional career and Jennifer, also as an attorney — we suspected that there were issues that Lorna was speaking about that were real. But we never in a million years would have expected the feedback that we received. To this day, every single day I hear from someone new that I didn't know who says, ‘This either happened to me or this is happening to me — and we need a better day.’

We've done quite a bit of work in a three-year period of time to make an immediate and long-term impact on the professional well-being and mental health of our healthcare workforce. I think we're in some ways just getting started on this work and just really honored and privileged to be in this space now, carrying on Lorna's legacy.

But really, this is for all the health care workers out there who need help. So they can take care of patients and just do their job.

DB: I'm so sorry for your loss and I just want to thank you for doing this in Lorna's name and legacy and really helping so many do better and be better. It's huge. Looking back, what are you proudest of having accomplished at the Foundation?

CF: The first thing I'm most proud of is that in that moment of clarity, we decided to act and speak out. It was a real testament to the human condition, particularly during COVID, when hundreds of people — thousands, really — offered help. And we took that help.

One of the humans that reached out was United States Senator Tim Kaine. He had read her story. And that conversation led to the first ever federal law looking out for the well-being of the healthcare workforce, called the Dr. Lorna Breen Healthcare Provider Protection Act, signed by President Biden on March 18th, 2022. That was quite a moment of pride.

As you know, as someone who's been in policy for a long time, it takes a long time to create new law, particularly at a federal level. We did this in 18 months. And we really view that law change as the first few steps of a whole body of law that's really looking out for the professional well-being and mental health of health workers.

Sticking with the policy angle for a second, we identified that there were at least six structural barriers or penalties to obtaining mental health care that apply to licensed health workers that apply in almost every state and almost every hospital they work in. And one of the most proud things we were able to do was we were able to develop a national badge recognition program and audit medical licensing across the country and begin to audit nursing and hospital credentialing applications.

For medical licensing, we've gone from 17 states that were compliant with our recommendations, which are basically consistency with the Americans with Disabilities Act for their questions on mental health — we've gone from 17 states when we started to now the majority of states.

That is progress. That is an impact that will be enduring for a very long time and will benefit thousands and thousands. Same on credentialing: we have now moved the vast majority of hospitals into credentialing in Virginia, my home state. We just heard earlier today from a very large health system that has over a hundred hospitals across this country that is going to use our recommendations.

So removing barriers and penalties to mental health access is absolutely one of our biggest feathers in our cap.

The other is that we've come together and brought together operationally all these different arms of health care. So right after we talk today, I'm going to be talking with the American Nursing Association and I have them in a campaign that we call All In: Well-being First for Healthcare. We brought together over a dozen of the largest national associations — who don't always get along, by the way — to lock arms around the well-being of the workforce. Collectively, they represent over a million health care workers.

We're scaling now a program called All In: Caring for Caregivers, which is the starter kit for hospitals and health systems. We have every single hospital in Virginia participating.

And then I would be remiss if I didn't point to the awareness work that we've been able to continue to drum up: speaking about this topic publicly, multiple appearances on morning shows, 60 Minutes, tons of publications.

In all of that, it's the stories that we get from healthcare professionals who reach out or stand up — like Dr Christopher Veal did at the American Society of Family Medicine Physicians, in Missouri earlier in the year. He stood up in front of all of his colleagues and he pointed at me and said, ‘Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation is the reason I spoke up about my mental health challenges and they've helped to save my life.’

And it's those kind of things — getting an email or a message through social media from someone who attended one of my talks who said, ‘Your words saved my life’ —that is what I'm actually most proud of, after all of it, that those people are here today because of the work.

DB: That's amazing. As you said, an 18-month span of time leading up to really momentous federal legislation.

I remember when I applied for a medical license in the state of California, it was much before your regulations had come into play and it was a very onerous application for somebody with a mental health condition — it required several hours of additional labor, cost, time. It was a nightmare.

And now I look at the questions on the exact same application, and they are so much better — so much more humane, so much more equitable. And it is literally thanks to the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation that that change has occurred now at such scale. It's truly remarkable.

CF: Thank you for saying that. And it's incredibly important now that physicians and other licensed healthcare workers know the rules. Every time I go to speak with groups of nursing students or medical students, and I ask them about obtaining mental health care, the vast majority, if not all of the room, says, 'We can't get help if we need it because there will be repercussions.'

And so now what we know is the enduring part of this work, once we make the change is to ensure that the workforce knows what the rules are. Physicians and other licensed healthcare workers deserve to know what the rules are. There should be no repercussions for getting mental health treatment.

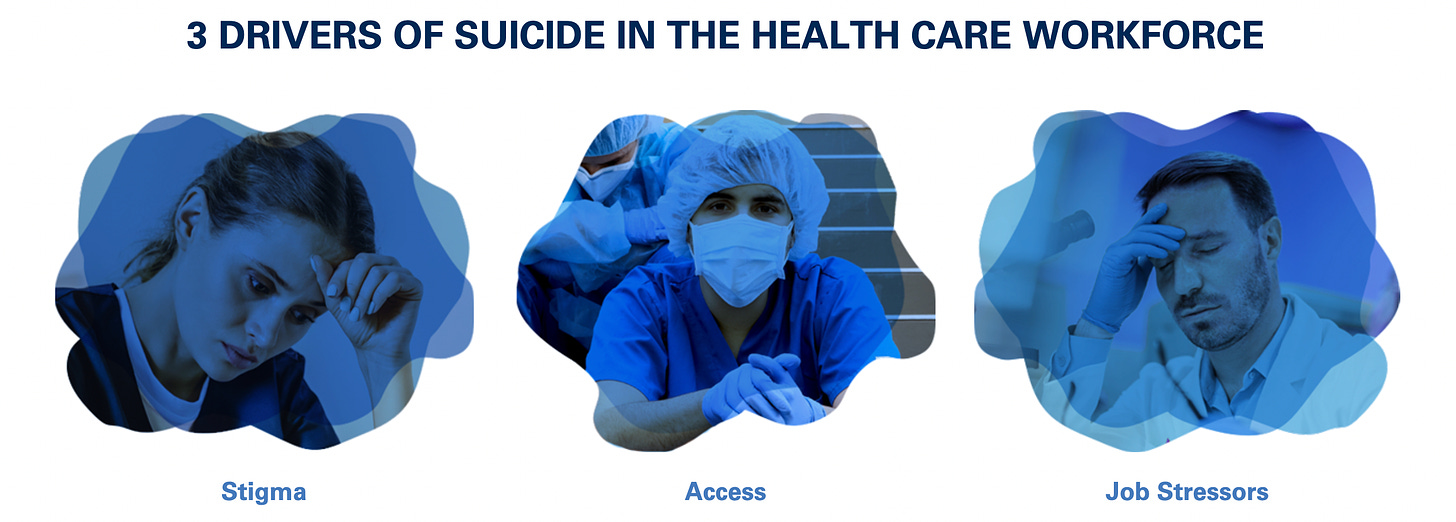

Within the last year, the American Hospital Association published their suicide prevention guide, identifying three key drivers of suicide.

The issue that we're talking about here is the number one key driver of suicide identified by the American Hospital Association. And that's a call to action to wake up — we lose 400 doctors a year to suicide in this country — at twice the rate of the general population.

You look at the rates of suicide and mental health by physicians in the United States compared to other countries, and they're the worst off. I think a lot of this has to do with the drivers around billing, compensation, and how the workforce is required to document everything it does while running as fast as possible on a hamster wheel, trying to push a boulder up the hill that keeps pushing them back down. How's that a mix of metaphors between a Sisyphus and a hamster wheel?

DB: Why is it that you think we still have the 24 to 28 hour shift in medical training, as well as in the physician workforce?

CF: I think there are a lot of things around the practice of medicine — which have been hidden and in plain sight for the general public — and have just been the way that we've always done it. Your example's a perfect one.

I'll contrast it with a flight crew. Everyone knows that if your flight is disrupted because your crew has been working too long, that's a safety issue.

I don't think the general public knows how long doctors and nurses have been working at any one time. You know, nothing magical happens when you graduate from residency where they count your hours at 80 hours a week to becoming an attending physician. Nothing magical happens in terms of your ability to sustain a prolonged amount of time without hurting somebody.

That’s the tragedy. In the airline industry, they did that for safety reasons for the passengers. If there was a real hard look at this — and there has been a hard look, particularly when it comes to nursing shifts — that after a certain period of time, the increase in medical errors rises. But it hasn't really been published very much.

I think back to when I was much younger, there was a Dateline episode on wrong site surgery. And that wrong site surgery was because a resident had been up for hours and hours and hours. And that led to a lawsuit. And it also led to limits on hours.

I think part of this is the general public doesn't know. The economics are not in favor of this. I remember the hue and cry across healthcare when we had to cap residency hours at 80 hours a week. Because it was going to require you to backfill those clinical hours with a higher paid person, a nurse practitioner or an attending physician.

So a lot of this is antiquated thinking. The rest of the world has moved on and has evolved in a much more employee- or workforce-friendly manner. Healthcare is one of the few that are lagging far, far behind.

At a basic level, healthcare workers need to know what their rights are. They need to know, if I go get therapy, ‘Am I going to have a consequence or not?’ And the answer should always be no. They also should know, ‘Do I have to work all these shifts?’

I was just on a panel at the Aspen Ideas Festival and there was a physician who runs a nursing recruiting firm. They put together employers and employees. And she talked about how important it was for hospitals to provide flexible shifts, because that's what nurses are asking for. But she was looking in her database and only a handful of hospitals were actually listening. The employees are speaking — and the employers need to adjust their operations, so that the workforce can thrive.

DB: Next, let's hear from Dr. Mona Masood, the psychiatrist who in 2020 founded the free Physician Support Line, staffed by volunteer psychiatrists to support physicians and medical students in a one-on-one and anonymous way. Mona, how did you come to this work?

MM: So I am an outpatient psychiatrist in the greater Philadelphia area and that has been my primary role for a number of years until March of 2020, the beginning of COVID as we know it in America. And at that point, many physicians — we found ourselves at the front lines of this kind of unprecedented pandemic. We're all trying to collaborate and share information from our various backgrounds and specialties on how to navigate all of this.

And in those discussions — tens of thousands of physicians all over the world on social media — I, as a psychiatrist was trying to do what I do, which is read between the lines of what people were posting… And yes, people are talking about diagnoses and imaging and treatment and all of that.

But there was a deafening silence in all of this: How are they feeling about this? How are they coping with all this? Where is the human in all of this?

I see the physician, but where's the human?

And this was a big red flag for a psychiatrist: They weren't talking about how they were feeling.

Physicians have a habit of intellectualizing: 'Give us facts, give us data, give us research.' We can really hide behind those things. But feelings — feelings are hard.

I remember one particular post from an ICU doctor in New York, 'Hey, does anybody know of a good lawyer? I want to write my will.'

Why would he be asking that, in this context? It's because he was thinking about his mortality — as all of us were, right?

And so I wrote my own post right after that one because it wouldn't leave me alone.

I wrote my own post, calling all psychiatrists, 'Who's with me?' — about starting a hotline for doctors navigating this pandemic.

And the response was quite incredible: 500 psychiatrists signed up within the span of a week. And then the support line started about a week later.

In that post, what I realized is we have to give permission to first talk about it.

DB: So this was to help people be human in this new moment, born of you feeling like physicians in particular were not acknowledging those pieces of their own needs. Was this on Twitter? I'm just curious. Was that the platform?

MM: No, it was actually on Facebook. I think there was a COVID-19 physician group: at the time, about 70,000 were on that group. Physicians from all across the globe.

DB: And how many physicians have come through? What have been some of the patterns you’ve seen?

MM: This is an anonymous support line. And we don't report to anyone in that regard in order to preserve the sanctity of the space.

But there are certain things that we log in order to make sure that we are meeting the needs of our callers: the subjects that people call about and also numbers.

We are tens of thousands of calls in — 4 years running.

With the start of the pandemic, people were calling in with imminent anxiety about what this could mean. Could they pass this on to their families? We were getting calls from people who were front-liners — ICU doctors, pulmonologists, infectious disease physicians.

I remember, because how can you forget? ‘I'm in the supply closet in my ICU. And I just need a moment to get a grip because I know I have to go back out there. I know that the patients need me, but I need to get a grip.’

And so sometimes, it was just holding space.

Sometimes, all you would hear on the other line is breathing. Sometimes all you would hear from the other person was, 'Are you there?' Just needing that reassurance that someone gets it and almost permission to even have any of these feelings.

We have debrief sessions between volunteers on a weekly basis.

And I remember that we were all surprised to find that most of these calls would start off with an apology.

The caller would be like, 'I'm so sorry for wasting your time,' when this is a deliberate line for this exact purpose. They would be like, 'I'm so sorry for calling. I know that there's people who could use this more than me. And if you need to go, I understand.'

These kinds of things are more telling than even what they would talk about. Physicians… we really, really do struggle with validating our own mental health.

MM: It went from the acuity of this whole time and survival mode — then callers would change the subjects to things that had nothing to do with COVID. Because we were physicians and struggling with our mental health prior to COVID, which we know, but wouldn't acknowledge it.

Then conversations would shift to family, like: 'Am I a good Mom? Am I a good Dad? Am I a good spouse?'

It would shift to political issues, because of course, we're affected by that, as well.

I remember when the whole tragedy with George Floyd happened, Black physicians were calling about how it felt to be a Black physician and how they felt triggered by all of this, and all the inequities that bleed into health care.

So what we realized from these conversations were that — behind the white coat, the stethoscope — doctors were still people who had the same thoughts and struggles as everybody else.

And that shared humanity piece became what we would give back to them in these conversations. Like, ‘That is something that you should be thinking about or caring about,’ or ‘You're not weird for having these thoughts or caring about things outside of medicine.’

DB: I'm curious about the volunteer psychiatry workforce. How many people are there? What do they do to support each other through this and to enable them to do it financially?

Great questions — and questions I had when I even put out that impulsive post.

I went in going, ‘Okay, a support line that makes sense — but what else makes sense?Anonymity. One person can't do this all on their own. We have to have volunteers.’

That part actually came pretty easily. People were really into that idea and were thinking about it themselves.

From there, we hired a lawyer, pro bono, who walked us through the policies and procedures and making sure that we were within our licensing, that we weren't acting as a physician, but more as a peer. We were not going to do continuity of care. And we're not going to prescribe medications.

Why it needed to be psychiatrists is that we were going to be able to apply various therapeutic modalities we were trained in, without needing additional training — it was already inherent in the field. So that's why we could start so quickly.

So we could standardize who you're talking to: These had to be actively licensed psychiatrists in the United States. We worked with a company who was going to vet that for us.

How we financially support this line is through a grant by the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Their owner and operator is Vibrant Emotional Health — they run the 988 number, and various support lines. They reached out to us at the very beginning when they started seeing us in various news platforms and said, ‘We want to support this.’

And we came back at them saying that it's incredibly important for the integrity of the line that it be run by physicians — because we have an issue with healthcare being run by people who are not in healthcare — so that would cause mistrust amongst our callers. We wanted to remain in control of the line.

And then within the group itself, we would have weekly educational seminars — again, pro bono — like the American Cross First Aid in Mental Health; experts on moral injury in health care; people from specific specialties talking about what’s unique about that specialty that causes burnout.

Weekly, we all meet together and we decompress: ‘What was hard for you this week; did you feel helpless? Or did you feel like you actually made a breakthrough?’ Sharing of knowledge and strategies — and also, we became friends [through this].

[If] I'm managing the line, I'm seeing missed calls come through because it's busy — I'll contact a volunteer and be like, 'Hello, friend — are you available to take a missed call right now?’

We have a census of 800 psychiatrists. We practice what we preach in terms of our own mental health and our boundaries. This is completely voluntary. We have signups on a weekly basis; we also have backup lists — if it's busy, they're able to sign on and take calls. On any given week, sometimes a [given] person will take 1 or 2 hours out of the week.

DB: And is this now your full-time work, or are you still doing other work?

MM: Oh, no, not at all. This is completely still volunteer. Even for me — I don't get anything out of it. I'm still a full-time outpatient psychiatrist. That's still my primary income.

We joke amongst the admin, that we were building a plane while we're flying it, essentially. We launched one week, but it's still in the process of becoming a nonprofit entity.

DB: Okay, so based on what you’ve seen in the last 3 and a half years, what is your sense of physician well-being: is it getting worse, staying the same, or improving?

MM: I do think it's getting less stigmatized. I will say there has been more acceptance of mental health as being a valid pursuit, a valid part of your health.

I am also seeing more advocacy among systems, which is what we actually needed. With any of these major movements, — BLM, women's rights, any rights — it's not just the individuals that protest, it's also the systemic reform that needs to happen.

And for physicians, we have a lot of systemic barriers to mental health [support]-seeking. There are states where their medical licensing applications definitely violate the Americans with Disabilities Act: they ask for treatment, previous medications, all this kind of stuff. So we've been working with the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation on language of licensing applications to de-stigmatize that on systemic levels.

A lot of my work — and what I was just doing right before our talk today — is I was talking to a medical school on mental health and systemic reforms. We have to change the culture of how we encourage each other about our mental health.

DB: Our third conversation today is with Ms Janae Sharp, CEO of the Sharp Index. To start, do you mind giving us a glimpse into how you came into this work?

JS: I feel like it just happened somehow — by life experience and by my decision to make a difference.

As background, I got married when I was 23. I don't know why we have to start there, but we do. And my husband [John Madsen] got his MPH; he went to medical school at Geisinger. We had three children.

During medical school, he had essentially a mental health breakdown, which he never really recovered from and he died by suicide; didn't finish his residency. And I went on, you know, to take care of our three kids.

I got a job doing stuff for patient reminders and went down the road to health IT and started writing about it. But I remained passionate about mental health. And I was going to speak at a conference and someone was like, 'Well, are you going to really make a difference here?' And I didn't have the complete answer.

But I knew that we needed more conversation about mental health. And I knew that largely, medicine didn't take mental health seriously. So I started Sharp Index to broadly to advance the mission to reduce suicide amongst physicians and healthcare workers, and improve clinician mental health.

I feel like we've been really lucky. We have so many amazing volunteers, especially data science experts, who are able to look at what technology can do and what would make a difference. We also have physician volunteers, and now we're subscribing to this great idea that health care should be the healthiest place to work.

If we really believe that health matters, and that the whole person matters, I think healthcare can be part of healing — even healing some of our larger societal problems that are reflected in care.

So, we work on lots of different stuff: we work on helping people individually and helping with narratives, whether that be talking to press or events, or helping communities.

We work with individuals who have lost someone, or physicians and healthcare systems who are struggling. I'm very proud of the work we've done for people who are in crisis or who have lost someone. Some of the stuff is long-term, like we have scholarships, we have aid — but when someone comes to you in crisis and trusts you or says, 'I lost this physician last week or maybe even several years ago, and I don't quite understand why I'm still feeling so connected to it,' that's very important.

I'm also proud that the way people talk about physicians is more human. It's less like us versus them. It's more this recognition that we've all been through a lot in the past few years and that we need to take care of everyone, including the people who will take care of us — or they'll leave.

But mostly I'm proud of the people who have come back and said, ‘You know, 'we could have ended up like John.’

Some people were there for me when that happened, but not the same way. There weren't a lot of people there saying, 'This is how you're going to feel and this is normal and this is one way to make it better.'

So I'm intensely proud of that.

DB: That's huge. Knowing everything you know in this space, what are your top tips for how to be there with somebody as they're recovering from a suicide loss? What should a community member or friend do or not do in that moment?

JS: Oh, that's a great question. I have a few top tips.

One is to know where you start and they end. When you're trying to be there for someone, it's really important to recognize that what they're going through is separate from you. And you might have big feelings: you might also be going through that loss. And you can be there for people and decide these are the things I can do to help, without trying to take on the whole weight of their pain.

I also think it's very important for people to realize that we don't really have a lot of education about grief, about death. It's culturally not something that we're very comfortable with. We don't sit there and grieve together in big groups. We have this culture of silence.

Learn about both how other cultures deal with this, but also decide what you want it to be yourself.

Grief is something you can learn about. And it's actually something that is more predictable than you would think and more normal — and also that we're not raised with.

When you're talking to someone about death, but you don't have any of the words to talk about what that feels like and you've never really seen it, it's a lot harder.

And I think my third tip is that you can carry people some of the way — you don't have to carry people all of the way.

And there will be times when you can do what you can do, and there will be times when you need to take the responsibility with your mental health to be healed and to be well. The entire process of our lives, I think, is that give and take. Recognizing how we can interact with other people, and when is the time that we need to heal, and when is the time that we need to help.

DB: You mentioned learning about how other cultures cope with grief. I'm wondering if there's one or two in particular that you think are better at it than we are.

MM: I think a study just got released about how people in Japan, when they're older, they live healthier, happier lives. And they have a greater acceptance of loss. So they particularly have a great reputation for being good at this. And also connecting young people with old people, connecting people with people who are struggling with mental health. They do better.

DB: I'm thinking more about that striking first tip — about knowing where you end and where that other person begins. I'm curious if you could say more about that.

MM: I learned it from having a family member with serious, ongoing chronic mental illness, where it wasn't really expected that that would go away.

And I think that profoundly changed the way that I approach everything with mental health. Like what if instead of saying, 'Oh, you're in crisis now, I'm going to fix you and let you go,' you said, 'This might just be how this person's brain works. And I need to decide what I can and can't do to still meet my obligations.'

Some people just need one-time help, but usually, we need healing that's more long-term.

And we also need to drastically alter our expectations for what other people will be doing:

We talked to a healthcare system who had a physician death a few months ago and the well-being team had had done a lot to help people and they still lost someone. And one of the hardest things that I heard was they just said, 'I just want to make sure this will never happen again.’ And that's something you hear a lot in suicide loss, especially with health care workers. And this is a Chief Well-being Officer. I wish I could have told them: 'You can't guarantee that. So what does your work look like when you can't guarantee it?’

For me, it means you still keep going. For some people, they shut down.

That's a larger philosophical idea about mental health where I think it's an expected disease, that we are fully capable of taking care of each other. [And] one person can't take care of all of one other person's needs or all of everybody's needs, but as a whole, we can.

DB: What have you found to be the most effective ways of supporting someone in crisis?

JS: A lot of the people who come to us in crisis are physicians. On several occasions, we've had a physician through our network just show up, sit with and talk to them. Showing up in person matters. We've also tried to do online support where people can meet with peers.

I've also found that there are two types of crisis. There's the acute crisis where they've kind of reached their breaking point and everything's spilling over. And then there's the crisis that's more prolonged that doesn't look the same, [but] largely is the same. So for those people, we found that going over truths without expecting a lot is important.

Usually when someone's in crisis, the thing they need most is someone to be there. Sometimes it's someone to go do their dishes — something very practical. Someone who will actively show up and not say, 'What can I do for you?' but will say, 'Look, we're going to go on a walk; we're going to go to lunch,' and take over and kind of carry that person for a while.

If you come bring someone a meal after a death, a lot of times, we're doing all we can, but they might still have a hard time two months later, if they're normal people.

DB: As you're looking at the field, what are the big bright spots — the places to feel optimistic or feel good about our progress?

JC: For me, the brightest spots are the individuals who keep sharing their stories. Chase Anderson shared his story — like, what is this actually like?

In addition, there are more people involved in policy and making it safe from a workforce perspective. I do like the Lorna Breen stuff — what they're doing with credentialing.

There are some things that we need to do that are not as popular.

Wendy Dean asked me the other day: ‘Is the cost of doing business [just] physician lives or patient lives?'

Sometimes the bright spot is that people are just leaving. People are saying no. Because you have to have people come together — striking. You have to have that for change. And that's not the most popular thing for people who are working with hospitals.

As a survivor, I'm like, 'All these people together, they can take power, and they can decide care is going to look different.'

And for me, that's a bright spot.

Because people have been pushed to do too much work for long enough.

Corey Feist, Dr Mona Masood, Janae Sharp on health worker well-being